Intolerance

Unafraid of the ugliness and destructiveness of grief and the strain of tragedy, Intolerance (Kûhaku), directed by Keisuke Yoshida, is a raw and nuanced examination of the flaws and frailty of people who suffer loss or trauma that pulls no punches in the narrative journey of its subjects.

Set in a Japanese seaside town, the audience is introduced to Mitsuru Soeda (Arata Furuta), a short tempered fisherman who lives with his socially withdrawn teenage daughter, Kanon (Aoi Ito). Her homelife tense, Kanon is soon caught shoplifting by store owner, Naoto Aoyagi (Tori Matsuzaka), who pursues her after she runs away down the street. This ends with Kanon being killed when dashing suddenly across the road. In the wake of her death, the film follows Mitsuru, who refuses to believe his daughter had shoplifted and blames Naoto for her death and much else, Naoto, who struggles to deal with the consequences of the incident, and the broader community including Kanon’s mother, Shoko (Tomoko Tabata), one of the store employees, Ms Kusakabe (Shinobu Terajima) and various others as the react and take sides in the ensuing recriminations.

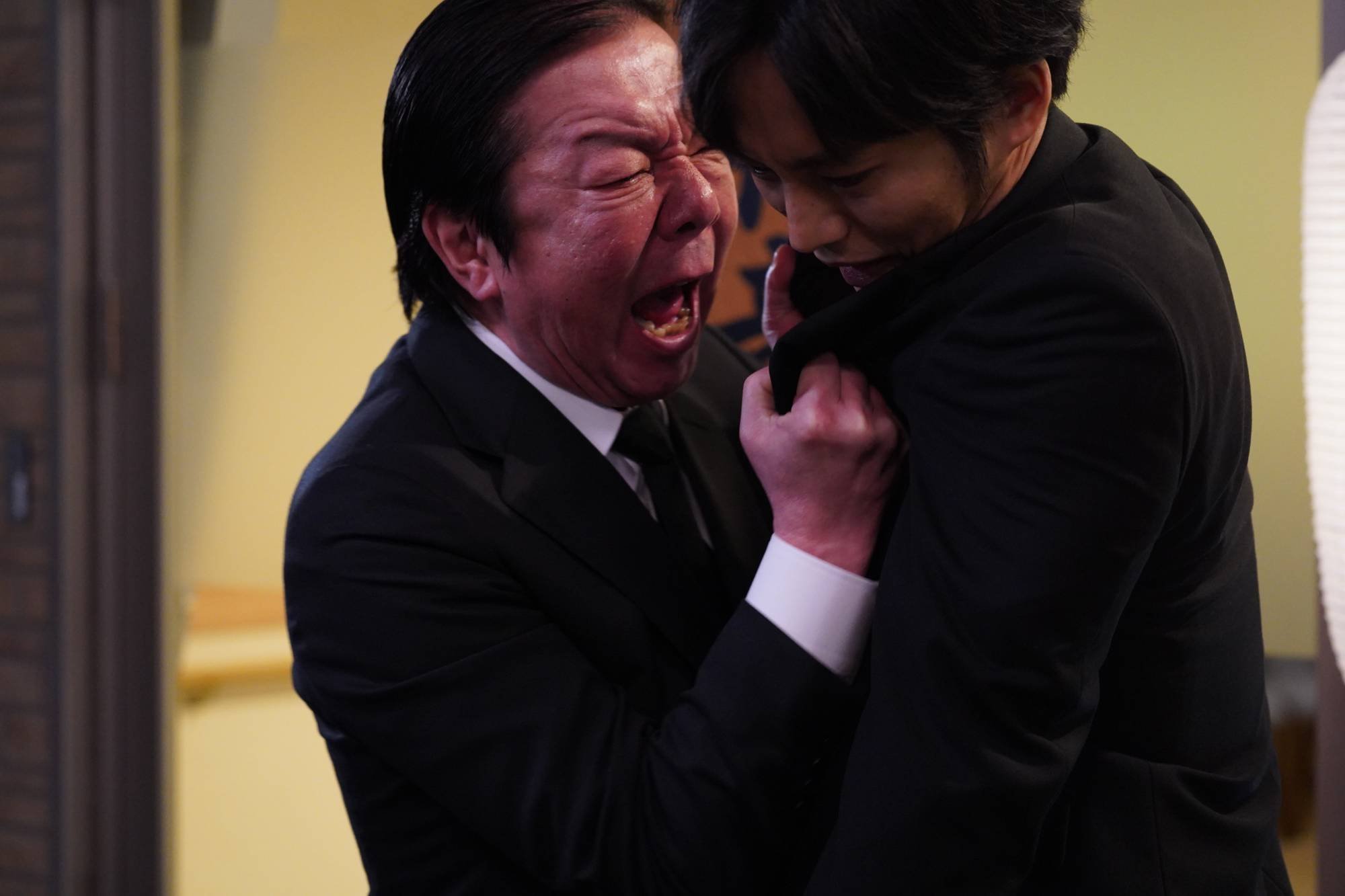

Intolerance is powerfully acted, with strong performances coming from the two male leads, who are well supported by solid contributions by their co-stars. Matsuzaka for his part does a commendable job of striking a balance between Naoto’s natural awkwardness and the emotional outbursts which are forced from him as the pressure on him builds. The shining star of the film, however, is Furuta as Mitsuru, who embodies the angry, self-isolated and lost divorcee. The strength with which Furuta depicts his character’s stubborn inability to accept his own faults and properly reflect on his daughter’s death is balanced expertly against a quiet tenderness that he is gradually able to find. Despite Mitsuru’s obstinance and outright bullying behaviour towards those around him, however, the audience is still drawn to sympathise as Furuta is able express, just below the surface, that there is a fragile and scared man who desperately wishes to protect his memory of his daughter and ultimately his own place as her father.

Intolerance is shot plainly, preferring directness in visual approach. This is mirrored by a sparse soundtrack, most scenes not supported by any backing track or theme. This proves an astute choice, leaving the audience with an honest and unadorned experience and is the more powerful for it. Indeed, visual or auditory flare would likely have diminished the intensity and impact of many of the scenes. A particularly striking example is the road accident, which has a brutal straightforwardness to it that shocks the viewer. Another is the closing scene which, without giving anything away, highlights the connection of Mitsuru to Kanon which he struggles to affirm throughout the film.

More than simply an exploration of grief, Intolerance is an examination of community and moral blame, as well as the oppressiveness that can be experienced by those who do not fit in or stand out in Japanese society. The media are depicted as vultures, interested more in portraying wrongdoers to be judged and criticised than doing justice by those affected by tragedy, whilst a community draws battlelines and condemn each other instead of understanding and healing. The film also is not out to create heroes or villains; the deep flaws of the major characters are on full display, and it is this that is its greatest strength.

Heartbreaking, visceral and above all satisfying, Intolerance is a fantastic offering for the Japanese International Film Festival 2022 and should be on the watch list of any fan of Japanese cinema.

Intolerance is playing as part of the Japanese Film Festival 2022 in Australia. Check out the full program and book tickets here.